Starts: Saint James Anglican Church

Tour Length: 10 km

Introduction

This 10km tour will take you through the most historic neighbourhoods along the Assiniboine river. Along the way we’ll talk about the history of our city’s western expansion, and the impact colonization left on the prairies.

Tour Stops

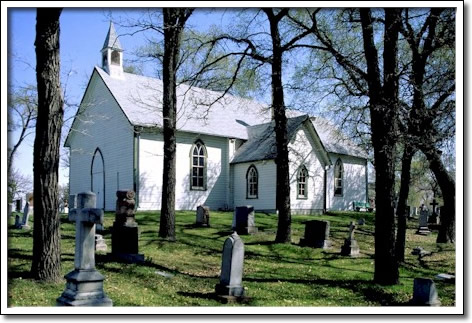

The oldest wood church left in Western Canada, it was built in 1853 on high ground that survived the disastrous 1852 flood. For this reason it was seen as a beacon and safe haven on the prairie. The Anglican Church had been directed to build a new parish here to help with westward colonization along the Assiniboine River. A settlement grew around this church, which later gave its name to the community of St. James.

Built in the Red River frame style of log construction for $1,620. It was located near a ford where the river could be crossed, and was allegedly built on or near an old Indigenous burial ground.

There was originally a tall tower on the building’s front, which was used by Riel’s men as a lookout post during the Red River Resistance. This led to its demolition in 1871. The church was restored to its current state in the 1960s.

St. James/Assiniboia

Today this area is known as St. James/Assiniboia. It began as a farming community that was mainly settled by families with Scottish & English-Metis heritage. The French-Metis community generally settled further upriver around St. Francis Xavier. Well outside of Winnipeg, this area remained relatively undeveloped until 1871. That year Treaty 1 was signed, which paved the way for further expansion west. Settlements quickly spread beyond the Forks & the older communities along the north/south Red River route.

Originally built as the Julia Clark School, part of the Children’s Home of Winnipeg. This organization was started in the 1880s to house orphans and later the children of soldiers during the First World War. At that time this area was agricultural and sparsely populated. This school was built in 1918 for the residents and named for a director of the organization.

The Children’s Home moved in 1945, and the building used as part of Deer Lodge Hospital. From 1958-1973 it was re-opened as the Assiniboia Indian Residential School, run by the Grey Nuns.

The Indian Residential School system is a notorious example of Canada’s colonial policies. Its stated goal was to eliminate Indigenous cultures and languages, and these schools were the site of countless human rights abuses.

The school has a very harsh design that is reminiscent of a prison. This style of architecture was very common for institutional buildings (like schools, prisons and military academies) in the early 1900s. It reminds us that these buildings were centres of authority. Among other things, they taught that a certain settler culture dominated this land. Today the story has come full circle, and the building houses the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

Originally the Manitoba Agricultural College, which was the first of its kind in Western Canada. It was built in 1905 by Samuel Hooper. At that time this was a very rural area, but by 1913 the neighbourhood had developed and the College moved to the University of Manitoba’s Fort Garry campus. This College became the nucleus that started the UofM.

It was then used as the first “School for the Deaf” in Western Canada. It later became a military hospital and was renamed the “Fort Osborne Barracks”. This confusing name came about when it replaced a real barracks on Osborne St, which was moved to build the Legislative Building. This was Manitoba’s main military base until 1968 when the Kapyong Barracks was built nearby. It was redeveloped into the Asper Jewish Community Campus in 1997.

This history has important links to many parts of Canada’s colonial history. Winnipeg’s rivers and railways made it the “Gateway to the West”, and a model for western expansion. It became the hub of agricultural settlement and industrial development across the prairies. It was also the centre of Canada’s military power in the west, which was used to enforce dominance over Indigenous peoples in situations like the 1885 North-West Rebellion.

Wellington & Tuxedo:

Wellington Crescent was originally a foot trail by the river, and this ritzy area was called “The Bush” until the mid-1880s. After the Richardson family moved here in 1889, all of the city’s richest followed. The street was named after lawyer Arthur Wellington Ross in 1893. The Tuxedo neighbourhood was planned in 1913 as an exclusive suburb. Its developers set rules for a minimum house price and lot size to stop any affordable housing from being built. These rules–and other unwritten ones–created a segregated community. Many of the beautiful original homes were patterned on Tudor & Georgian style English manor houses.

This is Winnipeg’s biggest park, and was originally called “City Park”. It was planned in 1904 by Frederick Law Olmsted, who is called “the father of landscape architecture in North America”. This became a common style across the continent, with curving walking paths, formal flower beds, and open lawns for picnics & games. A city zoo was planned here from the beginning. It was designed to be winding and rolling like the English countryside, to “provide relief” from the gridlock of urban streets.

The park was built well outside the edge of Winnipeg. This was an intentional urbanization strategy, with the City reaching out to connect with the suburb of St. James. They knew development would follow the park.

The Pavilion first opened in 1908 and burned down in 1929. This new replacement was built in 1930, but the pond and pergolas behind it are original. Originally used for banquets and events, it now holds an art gallery.

The building was meant to represent old-world Europe, imitating the iconic Tudor-style English cottage with half-timbered & stucco construction. It was designed to tower over the park and be a clear focal point of English culture, which would attract settlement to fill in the prairies.

The statue in front of these formal English-style gardens is called “The Boy with the Boot”. It was given to the City in 1897 by the “Young People’s Christian Endeavour Society” and originally stood in front of city hall. Unbelievably the statue was stolen and stayed missing for 30 years. It was mysteriously left next to the nearby Duck Pond in the 1940s and given a new home here.

These gardens represent the replacement of natural prairie with foreign plants and man-made landscapes. It is only in recent years that the leisure value of our natural prairie landscape is being appreciated, with the nearby Assiniboine Forest and its wetlands. When we consider its history and the ideas behind its design, Assiniboine Park can be seen as a symbol of colonial power over this land. Indigenous prairies were bulldozed so that designers could recreate an English countryside. Institutions like residential schools are an obvious kind of oppression, but parks and urban design were also part of a ‘civil colonization’. Neighbourhoods were built to look like England instead of Manitoba. Parks were designed to look artificial and foreign, instead of celebrating the nature that surrounds us. The way we experience the world around us shapes our ideas, and people here were intentionally separated from the land where they live.

A little further to the west is a point called The Passage. Shallow points in the rivers created natural fords, or crossing points. Bison herds used these fords and hunters followed them. Later fur traders also depending on them, and river ferries were common in Winnipeg until the early 1900s.

Unlike the neighbourhoods we just rode through, areas west along the Assiniboine were mostly settled by French-Metis families. The nearby town of St. Francis Xavier was originally known as Grantstown, after its founder, Cuthbert Grant Jr. He is also known as the father of the Metis Nation.

The Hudson’s Bay Company controlled the settlement around the Forks that would grow into Winnipeg. Many rural Metis families worked for the rival North West Company, and they saw their lifestyle and land being threatened by the new settlers. This led to a long conflict known as the Pemmican War.

Tensions boiled over in 1816 at the Battle of Seven Oaks. A Metis force led by Cuthbert Grant won a dramatic gunfight and 21 people died, including the Governor of Red River. Grant’s men destroyed the small Red River Settlement, but it was rebuilt within a year after the HBC brought in mercenaries and more settlers. Grant’s force travelled across The Passage and would have passed by this spot on their way to the Battle.

Grant’s Old Mill sits in an extensive park along Sturgeon Creek. This land was nearly lost when the City tried to sell it to developers in the 1970s. It took a major community campaign to save it, but it is now protected and being returned to naturalized areas.

The building is a re-creation of a mill that Cuthbert Grant owned somewhere along Sturgeon Creek in the 1830s. This accurate replica was built by a dedicated group of community volunteers in 1973, and it still actively grinds grain into flour.

Grant was born in 1793 to a Scottish fur trader and a Metis mother. He was sent to Scotland to be educated, then returned to Manitoba and worked in the fur trade for the North West Company. After his involvement in the Battle of Seven Oaks, the Canadian government put him on trial and acquitted him of any wrongdoing.

Grant built the first water mill in Western Canada near here in 1829 to serve the surrounding farmers. Unfortunately his business venture was also a complete disaster: The mill’s dam was repeatedly destroyed by spring flooding, and it was abandoned 3 years later. Grant was later hired by the HBC as “Warden of the Plains”–a position like a sheriff who policed the fur trade. He was given land to the west, where he brought 100 Metis families and established Grantstown (today’s St. Francis Xavier). This community became famous for its wheel-makers, who made the Red River carts used for shipping furs and supplies across the prairies.

This site holds two contrasting buildings that speak to the area’s evolving history.

To the left is an 1856 Red River frame-style log house, built for William Brown (HBC labourer from the Orkney Islands) and Charlotte Omand (English/Anishinaabe). The Omand’s were a prominent Metis family in the area who gave their name to Omand’s Creek.

William and Charlotte originally settled in St John’s, near Seven Oaks House Museum. After the flood of 1852 they moved to Headingly to farm and built this home. It was originally a one-room cabin, with an addition built after 1890. It was-moved here in 1973 to save it from demolition and help create the Historical Museum of St. James-Assiniboia.

By the turn of the 20th century the City of St. James had developed from farmland into a suburb of Winnipeg. Streetcar service extended all the way from downtown to Deer Lodge by 1903. While the Deer Lodge area around Assinboine Park was fully developed by the 1920s, this western area (Assiniboia) remained rural until the 1940s.

The brick building is the The RM of Assiniboia’s Municipal Hall. It was built in 1911 and used as a city hall, school, and police station until St. James became part of the City of Winnipeg in 1972. It has a very unique-looking enclosed fire escape on the back.

In contrast with the local, Manitoban-style of the Red River frame cabin, this type of building was a common design that could have been found anywhere in North America in the early 1900s. The architecture has its charms, but it is another example of the way our home moved away from local traditions and lost much of its unique identity as it urbanized in the 20th Century. We’ve talked about the role urban planning played in colonialism, and most cyclists will understand that cities have been built to separate us from the land and from each other. For many people, roads control their entire experience of the world around them. When we explore Winnipeg on our bikes, we’re following the rivers and seeing our home much more like people did in the past. We’re getting back in touch with the land we live on, and reflecting on our shared history in a new way.

The Pedal into History project was supported by contributions from the Province of Manitoba through the Heritage Grants Program., the City of Winnipeg, and Seven Oaks House Museum. We are grateful for their support.