Starts: Le Musée de Saint-Boniface Museum (454 Tache)

Tour Length: 10.75 km

Introduction

St. Boniface was one of the earliest parts of Winnipeg to be settled, after the Seven Oaks area.

It has always been our city’s French quarter and it has largely maintained its unique cultural character to the present day. Still, the neighbourhood has seen many changes and challenges related to its identity: Politics have led to clashes between English & French, Protestant & Catholic, Indigenous & settler communities.

The area is filled with rich architectural resources. Today we’ll be visiting buildings dating back as far as the 1850s and 1870s. We’ll see how diverse architectural styles evolved in response to different influences as the community grew. St. Boniface was also a center for trade, with its ideal location near The Forks and the Seine River. The first rail lines arrived in St, Boniface before Winnipeg, spurring heavy industrial growth in some areas. This unique geography and complicated industrial history means that today, St, Boniface offers incredible bike trails and park spaces along the rivers.

We’ll start in the heart of Franco-Manitoban culture: Old St Boniface, before stretching our legs for a ride south into the Anglo suburb of Norwood.

Tour Stops

St Boniface grew up around the earliest Catholic mission, which was established here in 1818. The Grey Nuns arrived in 1846 with the goal of spreading Catholicism to Indigenous peoples.

Their Convent was built between 1846 and 1851 using oak logs in a variation of the local Red River Frame architectural style. It is the second oldest building in Winnipeg (you can visit the oldest on our Ride the Red tour.) The nuns lived here, but they also set up an early school, cared for orphans and established the first hospital in Western Canada, which would grow into St. Boniface Hospital. The Grey Nuns also operated the only two Indian Residential Schools in Winnipeg. They left the convent in 1956, and in 1967 the St Boniface Museum opened inside.

The mill stones nearby were used in the Riel family’s grist mill, which was located along the Seine river. Also note the statue of Louis Riel, who was a student of the Grey Nuns here. St Boniface was an important hub for the Franco-Metis community and it would become the center for political organization under Riel – a man frequently considered the father of Manitoba.

Winnipeg only took on the form we know today in 1972, with the signing of the Unicity Agreement. Before this date, most of the areas we now recognize as neighbourhoods (St Boniface, St James, St Vital, West/East Kildonan, etc) were independent municipalities with their own governments and services. By the late 1800s the riverfront had lost its fur-trade importance, and Provencher Boulevard became the heart of the modern Town of St Boniface. This street was the administrative, banking, business & retail hub for the east bank of the Red River. Even as the community grew, its location across the river from Winnipeg itself, and its long history of Francophone pride and political resistance ensured that it retained much of its unique language and character.

St. Boniface City Hall was designed alongside its firehall by local architect Victor Horwood and was completed in 1906. The main floor held municipal offices, with council chambers on the second floor, and a penthouse residence for the Chief of Police on the third. Eleven jail cells and the local courtroom were located in the basement. Today the building is being used as Maison des Artistes Francophones, with a gallery inside and an incredible sculpture garden on the grounds.

St. Boniface Fire Hall No.1 was built in 1907. While most contemporary fire halls around Winnipeg are identical, this one was designed in a unique style by local architect Victor Horwood. It was used as a fire station until 1967, when it reopened as a Fire Hall Museum, and later an office and a seniors’ drop-in. Today its future is uncertain, as community members are resisting attempts by the City of Winnipeg to sell the property.

The Grey Nuns themselves are nearly gone, with only a few very elderly members left, but the institutions they established still play central roles in the community. L’Universite de Saint-Boniface is the primary center for francophone learning west of Quebec. The original College was built in 1880 and was nearly twice the size of the current complex. It caught fire and burned to the ground in 1922, killing 10 people. The present building was donated by Archbishop Arthur Beliveau, and has had numerous additions made over the years.

Following Louis Riel’s role in the birth of Manitoba, he was labeled a traitor by the Canadian government and was forced to flee to the United States. He would return to lead a second resistance in 1885, ending with his execution. While he was a strong leader, history suggests that he was also a tormented man who may have developed serious mental health issues and religious delusions during his exile. You can learn more about this exciting story on our Birth of a Province tour.

Note the twisted, expressionistic depiction. The artist intended to show Riel as a tortured man, who suffered for his noble actions. It was originally placed outside the Manitoba Legislature in 1973 but was deemed to be undignified and was replaced with a new statue by the Manitoba Metis Federation in 1991. The sculptor chained himself to it in a protest, unsuccessfully trying to prevent its move.

Across the street is the Dominion Post Office Building. It was constructed in 1907 by the prominent local builder, James McDiarmid. It uses a kind of “stock architecture” employed for post offices across the country, with a design by the Chief Architect for the federal Department of Public Works. Today it remains an important meeting place for the neighbourhood as a local cafe.

Kittson House is a very old and special home built in our local Red River Frame style of architecture. Underneath the paneled exterior and verandah, it has a frame of hand-cut logs which are notched together using mortise and tenon joints. It has been well-maintained and cosmetically updated over the years, and is now one of the oldest houses still in private hands. It was built in 1878 for Alexander Kittson, a prominent but short-lived politician. He died of smallpox in this home at the age of 30. It was later owned by musician and former director of the St Boniface Museum, Marius Benoist. The house was originally built at the intersection of Provencher Boulevard and Rue du College, until it was moved here in 1946.

Beyond the area’s French character, we need to recognize that the Metis community played a central role in the development of St Boniface. From the moment Europeans arrived in Manitoba, there was extensive intermarriage between settlers, traders & Indigenous women, leading to the emergence of the Metis people, along with the Michif and Bungee languages. We already met Louis Riel, but Eleazar Goulet was a less-prominent figure who was also involved in the birth of Manitoba. Goulet was the first mailman in the Red River Settlement, fulfilling an incredibly important role. He was quite literally our home’s only connection to the outside world; traveling alone to Pembina, North Dakota several times a year carrying the Settlement’s mail. Goulet worked with the Ross Family, whose home was used the first post office in Western Canada. Ross House Museum is open for tours every summer.

Following the Red River Resistance in 1870, the Government of Canada dispatched the military Wolseley Expedition here to pacify the Settlement. Wolseley’s troops engaged in a campaign of terrorism and vengeance against the Metis community, and Goulet was attacked one day after he was caught on the opposite, English side of the river. He was chased into the water near this point and was stoned to death as he tried to swim across to safety. This commemorative park is built in the shape of the infinity symbol used on the Metis flag.

This style of round brick water tower has been in use since the Roman empire over 2,000 years ago. This particular tank was built in 1919 when the Shoal Lake Aqueduct was completed. The aqueduct was built to supply Winnipeg with clean drinking water following several deadly epidemics of typhoid fever. Before then, drinking water was either taken directly from the polluted Assiniboine River, or shipped into the city in barrels. The aqueduct was an engineering marvel that continues to provide our city’s water to this day, but it also turned Shoal Lake 40 First Nation into an island with extraordinarily difficult living conditions. A year-round road was only built to the community in 2019, and they still do not have access to clean drinking water of their own. In the early 1900s, this site was also home to a bridge which ran to downtown Winnipeg.

As we ride to our next stop, we’re going to pass by Fort Gibraltar. This is a replica of a fur-trade era fort which was built by the North-West Company on the other side of the river, in an attempt to control The Forks during struggles with the rival Hudson’s Bay Company. This conflict over 200 years ago sowed the seeds of distrust between French and English settlers, and culminated in the bloody 1816 Battle of Seven Oaks, where the Red River Metis Nation first asserted their rights to this land and killed the local Governor.

A few isolated riverbank areas like this preserve the last remaining old growth cottonwood trees in Winnipeg. Stopping here on a quiet day will take you back to a time before the city – even long before the Settlement. Imagine a time when massive trees like this covered much of the landscape, instead of being incredibly rare. The first voyageurs and our province’s diverse Indigenous nations traveled through paths like this to trade, hunt, and live. Riverbanks provide natural routes to follow, and we’re riding along trails that have been traveled by countless generations on foot, horseback and bicycle.

In the 1920s, Whittier Park was home to a large horse racetrack, almost like an early Assiniboia Downs. The other side of the park was used by CN Rail as their rail yards, with numerous shops. After the rail yards left, the area was slowly reclaimed into a large, semi-wilderness park. Ambitious explorers can still find the ruins of the CN shop buildings buried in the bush at the end of some trails.

Remember the millstones from St Boniface Museum? The Riel family owned a mill located on property that stretched the entire length between the Seine & the Red rivers. The mighty Red River and the various tributaries connecting to it were the entire reason our city was established here.

You might be surprised to learn that the very first settlers in St Boniface arrived in 1817 and were not French, but Swiss. In the aftermath of the Battle of Seven Oaks, members of the Des Meurons Regiment served as mercenaries for Lord Selkirk, the Scottish nobleman credited with founding the Red River Settlement. As a reward for their service, they were given land to farm along the Seine River. Most of the Swiss community left after a disastrous flood in 1826, but Des Meurons Street is named for them.

A strong Belgian community also grew within St Boniface in the late 1800s. Le Club Belge formed around the turn of the century and met at various locations in Winnipeg and St Boniface for several years. In 1908 they built the Belgian Club using a loan from the McDonagh and Shea Brewery. The Club was a success, with a second storey added three years later, and a further extension added to the east side in 1914. The Club still operates with a two-lane bowling alley, lounge, and bar inside.

Just south of the Belgian Club is the Belgian Veterans Association Historical War Memorial. The monument was unveiled on October 1, 1938 to commemorate veterans who served in the First World War. The statues of the soldiers are remarkable because they were carved directly from stone, and not cast in bronze. It was designed by local sculptor Hubert A. Garnier and modeled on two local residents named Alfred De Cruyenaere and Julien Buysse.

Holy Cross Roman Catholic Church was dedicated on December 10, 1922, and is the oldest English Roman Catholic parish in St. Boniface. The building suffered a major fire in 1990 but has since been restored. You might notice that this church has a very distinctive style of construction when compared with the numerous French Catholic churches in this neighbourhood. Its cobblestone facing and square, solid style is a clear imitation of medieval British church architecture. In some ways we can understand this church as a strong cultural symbol sitting atop the hill, signaling a British presence in an area that we normally think of as French.

This unique building is very recent compared to the rest of our tour, but it’s too special to pass up. L’Eglise de Precieux Sang is a remarkable example of local modernist architecture, which has been widely recognized outside of Winnipeg. It was built in 1967 based on designs by Etienne Gaboury, a tremendously influential modernist architect. In the 1960s the Catholic church actively tried to modernize its image, in part by stepping outside of traditional rules for church architecture and embracing creative designs.

St. Philip’s Anglican Church was built in 1904 and was used until approximately 2020. It was recently converted into condos, in an interesting example of the adaptive re-use of a heritage building. The monument standing beside it was designed by local resident Leonard W. Meanwell in 1920, to commemorate members of the congregation who were killed during the First World War.

This south-western corner of St Boniface is called Norwood, and it has a distinctly different character than the rest of the area. Norwood was a planned “suburb” of Winnipeg that was marketed specifically to the English-speaking community. There were political reasons to encourage Anglo settlement within historically French districts, and language rights became an incredibly divisive issue at the turn of the century during debates around “The Manitoba Schools Question”. Development often provided an opportunity to shift demographics and gerrymander electoral districts.

This land was originally The Norwood Ball Grounds, but by the 1930s it was primarily used as a dump. In 1937, a group of citizens formed the Coronation Park Committee and raised funds to clear and landscape the grounds. The park opened on May 12, 1937 – the day of King George VI’s ascension to the throne. A large cenotaph stands in the middle of the park, commemorating veterans of the First and Second World Wars.

Much like the Post Office we saw along Provencher Boulevard, the Dominion Post Office Building was built using a template design produced by Thomas W Fuller, Chief Architect for the federal Department of Public Works. It was constructed in 1935 by local architect George Northwood and the Claydon Construction Company. The building is notable for its imposing and ornate brickwork, with towering peaks above each corner that almost suggest a castle. The post office was built as a central government building for the growing Norwood area, and a significant commercial strip grew up around it.

This towering warehouse was built in 1919 for the Warshall-Wells hardware company, and then came to house the International Laboratories Limited. Their huge factory produced a variety of chemical industrial products like paint and soap. A more significant historic site is no longer visible here, but it would have sat next door:

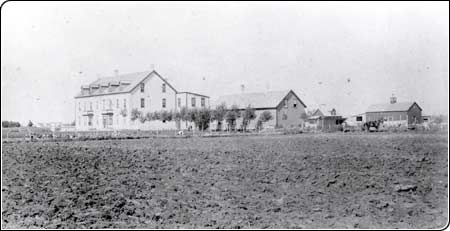

The St. Boniface Industrial School was a little-known Indian Residential School, which operated briefly on this site from 1890 to 1905. It was opened by the Grey Nuns, who also ran the Assiniboia Residential School, Winnipeg’s primary Residential School. You can learn more about this dark chapter in our Across the Assiniboine tour.

The Industrial School had a massive 40-acre property, where industrial and domestic vocational skills were taught. It was closed in 1905 due to low enrollment, after which the government started legally compelling people to send their children to Residential Schools which were built in more rural areas. The remaining building burned in 1911. This site is an important one to remember, when we consider that the community of St Boniface originated around a Catholic mission. The colonization and Christianization of Indigenous peoples was a core part of the area’s history.

We’ll end our tour on a happier note, with the sunny yellow exterior of Maison Gabrielle Roy. This was the childhood home of the renowned francophone author Gabrielle Roy. She won international awards for her first novel, published in 1945, along with three Governor General’s awards. The 1995 book Rue Deschambault (published as “Street of Riches” in English), was named for the street we’re standing on, and vividly describes her early life in old St Boniface. Her home was carefully restored and opened as a museum in 2003.

Roy was an important icon for Franco-Manitoba culture, and her writing offers an opportunity to learn some of the history we’ve been discussing from a personal perspective. While we often think of St Boniface simply as Winnipeg’s French quarter, this tour has shown you that it has a rich history of diverse communities and perspectives – all of which have left a wealth of architecture and stories for us to explore.

The Pedal into History project was supported by contributions from the Province of Manitoba through the Heritage Grants Program., the City of Winnipeg, and Seven Oaks House Museum. We are grateful for their support.